World Development Report (2015)

by 趙永祥 2017-05-07 11:29:33, 回應(0), 人氣(908)

2017-05-07 11:29:33, 回應(0), 人氣(908)

The trends of Mind,Society and Behavior

http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2015

Summary on this Hot Issue

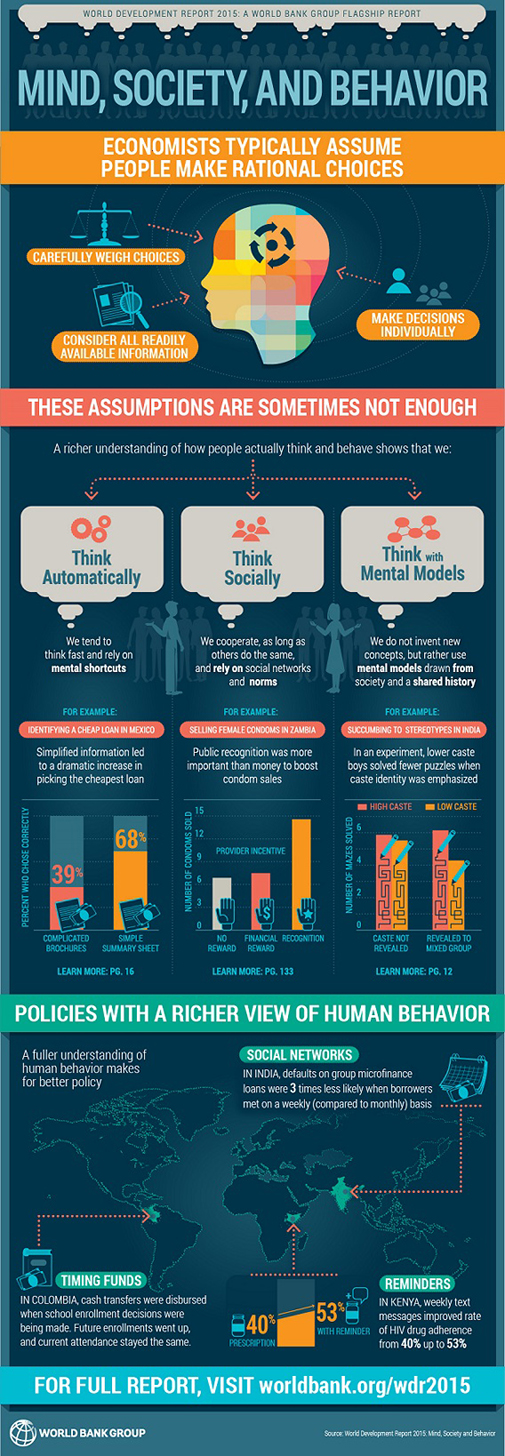

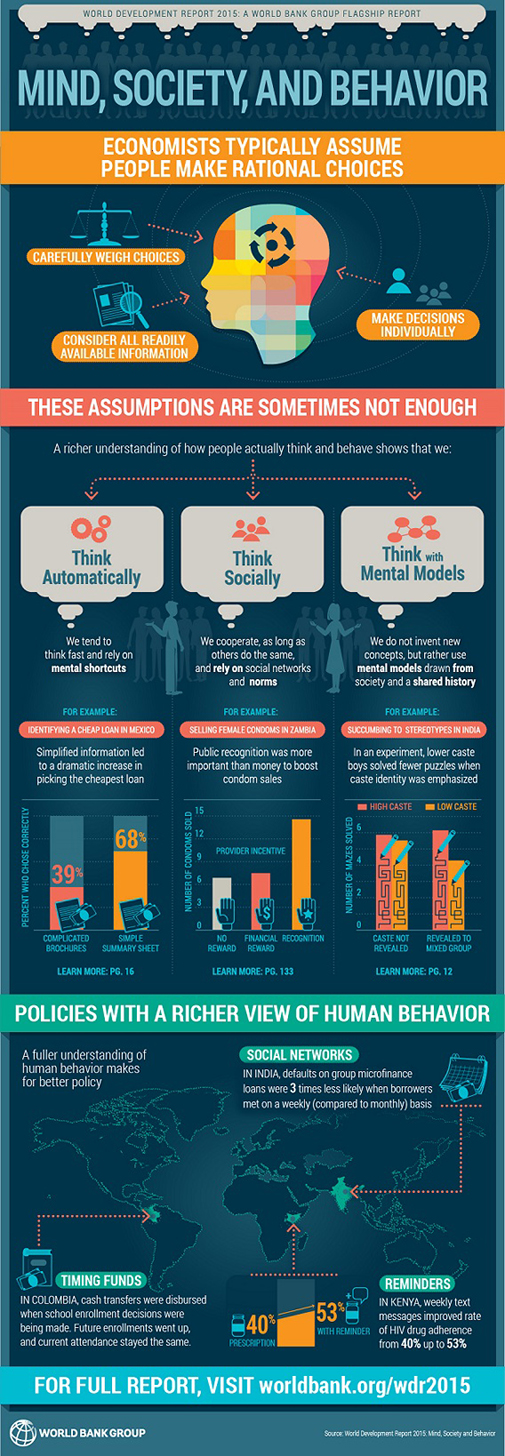

Every policy makes assumptions about human

behavior.

Public policy typically subsidizes and publicizes

activities worth encouraging and taxes those

to be discouraged. Underlying this approach is the

notion that human behavior

arises from “rational”

choice: individuals carefully weigh their choices,

consider all readily available information, and make

decisions on their own. Policies arising from

this perspective

focus on changing the benefits and costs of

individual actions, and have proven very effective in

many domains.

In recent decades, however, research on decision

making has cast doubt on the extent to which people

make choices in these ways. Novel policies based on a

more accurate understanding of how people actually

think and behave have shown great promise, especially

for addressing some of the most difficult development

challenges, such as increasing productivity,

breaking the cycle of poverty from one generation to

the next,

and acting on climate change.

Three principles of human decision

making

To understand and apply recent findings on human

decision making, this year’s World Development

Report presents a framework

that relies on three

principles:

1. Thinking automatically.

Much of our thinking is

automatic and based on what comes to mind

effortlessly. Deliberative thinking, in which we

weigh the value of all available choices, is less

common. We use mental shortcuts much of the

time. Thus minor changes in the immediate context in which decisions are made can have disproportionate

effects on behavior.

2. Thinking socially.

Human beings are deeply social.

We like to cooperate—as long as others are doing

their share. Institutions and interventions can be

designed to support cooperative

behavior. Social

networks and social norms can serve as the basis

of new kinds of

policies and interventions.

3. Thinking with mental models.

When people think,

they generally do not invent concepts. Instead,

they use mental models drawn from their societies

and their shared histories. Societies provide

people with multiple and often conflicting mental

models; which one is invoked depends on

contextual cues. Policies and interventions to

activate favorable mental models can make people

better off.

Psychological and social perspectives

on policy

These three principles have major implications for

development policies and interventions. Interventions

need to take into account the specific psychological

and social influences that guide decision

making and behavior in a particular setting. That

means that the process of designing and implementing

effective interventions needs to become a more

iterative process of discovery, learning, and adaptation.

What matters is not only which policy to implement,

but also how it is implemented.

In addition, experts, policy makers, and development

professionals must recognize that they, too,

are subject to social and cultural influences, and think automatically.

They tend to select and filter

evidence in ways that confirm their prior views.

Their social contexts can lead them to misunderstand

how people living in poverty make decisions

and behave. They need to become aware of their

own biases, and development organizations should

implement procedures to mitigate the adverse effects

of these biases.

Seen under a psychological and social lens, poverty

is more than a deprivation in material resources.

The stresses and strains of poverty impose “taxes” on

cognitive resources.

Policy makers should try to move

crucial decisions out of time periods when mental resources

are especially scarce.

They can, for example,

shift school enrollment decisions to periods when

poor farmers’ seasonal income is higher. They can

also target assistance to important decisions that

require a lot of cognitive resources, such as applying

to a higher education program.

These ideas apply to

any initiative in which program take-up is a challenge.

Poverty early in life also affects psychological resources.

High stress and insufficient socio-emotional

and cognitive stimulation in the earliest years can

impair cognitive development.

Programs that provide

very early childhood stimulation can have a

large impact on adult success.

Adopting a psychological and social perspective

enlarges policy makers’ toolkits. For example, simplifying

decisions can help people make choices that

better serve their interests. Enrolling in government

programs is often too difficult, and household finance

decisions require considerable cognitive resources.

It is easier for consumers to determine which

loans and savings products are best when they are

presented with succinct summaries of savings rates

and loan costs.

Financial literacy programs are more

effective when they teach rules of thumb instead

of a

standard financial education module.

Using reminders is another new tool to help individuals

execute their plans. Weekly text message

reminders can help patients take their medicine

regularly. Reminders about late fees on loans improve timely repayment. But reminders need to be appropriately

tailored; those that cite specific reasons for

saving can be twice as effective as generic messages.

Commitment devices can help people act

on their

intentions by locking them into a course of action,

such as eating more healthy foods, working harder,

or saving more.

In many cases, around one-third of

individuals who are offered commitment devices

(often in the form of fees or financial penalties for

failing to meet their own goals)

accept them.

Social incentives can be as effective as economic

ones. Informing people how much energy they consume

compared to their neighbors reduces average

consumption. Publicly praising people who conserve

water and reproaching those

who do not can help a

city avert a water supply crisis because people tend to

conserve more when they have assurance that others

will also conserve.

Social awards, gifts, non-monetary

prizes, and recognition can lead people to work

harder. Many programs are more effective when they

are channeled through peers and networks, rather

than through the individual alone.

Entertaining educational narratives can drive key

development choices. Television and radio shows

that incorporate social messages can reduce teenage

pregnancy, improve savings rates, and increase women’s

autonomy.

Aspirational messages can increase

parents’ investments in their children’s education

and school performance.