It’s anniversary season this Fall, although commemorating ten years since the financial crisis

may not be the kind of party we should be poppin’ bottles for. We’ve had a recovery, to be sure,

although it has been rather uneven – especially for people on the lower end of the income bracket with little to no investments or savings. Unfortunately, those people represent nearly half of the

U.S., and while there may have been easy money to be made given ultra-low interest rates and

other stimulants, too many hard working people had no means to take advantage of them.

The aftermath of the crisis produced reams of new legislation, the creation of new oversight agencies that amounted to an alphabet soup of acronyms like TARP, the FSOC and CFPB – most

of which barely exist today – new committees and sub-committees, and platforms for politicians,

whistle-blowers and executives to build their careers on top of, and enough books to fill a wall

at a bookstore, which still exist… I think.

Let’s get some of the shocking statistics out of the way, and then we can dive into the lessons –

both learned and not learned – from the crisis:

- 8.8 million jobs lost

- Unemployment spiked to 10% by Oct 2009

- 8 million home foreclosures

- $19.2 trillion in household wealth evaporated

- Home price declined of 40% on average – even steeper in some cities

- S&P 500 declined 38.5% in 2008

- $7.4 trillion in stock wealth lost from 2008-09, or $66,200 per household, on average

- Employee sponsored savings or retirement account balances declined 27% in 2008

- Delinquency rates for Adjustable Rate Mortgages climbed to nearly 30% by 2010

There are many many more statistics that paint the picture of the destruction and loss surrounding that era, but suffice to say, it left a massive crater in the material and emotional financial landscape of Americans.

We’d like to believe that we learned from the crisis and emerged as a stronger, more resilient nation. That is the classic American narrative, after all. But like all narratives, the truth lives in the hearts, and, in this case, the portfolios of those who lived through the great financial crisis. Changes were made, laws were passed, and promises were made. Some of them kept, some of them were discarded or simply shoved to the side of the road as banks were bailed out, stock markets eclipsed records and the U.S. Government threw lifelines at government-backed institutions that nearly drowned in the whirlpool of irresponsible debt they helped to create.

To be sure, policymakers made critical decisions in the heat of the crisis that stemmed the

bleeding and eventually put us on a path to recovery and growth. It's easy to Monday morning

quarterback those decisions, but had they not been made with the conviction and speed at the

time, the results would likely have been catastrophic.

Let’s examine a handful of those lessons for some perspective:

1. Too Big to Fail

The notion that global banks were ‘too big to fail’, was also the justification lawmakers and Fed

governors leaned upon to bail them out to avert a planetary catastrophe that may have been

several times worse than the crisis itself. To avoid a ‘systemic crisis’, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was passed, a mammoth 2,300-page piece of legislation authored by former Congressmen Barney Frank and Christopher Dodd. The Act give birth to oversight agencies like the Financial Stability Oversight Council and the Consumer Financial Protection Board, agencies that were intended to serve as watchdogs on Wall Street.

Dodd-Frank also subjected banks with assets over $50 billion to stress tests and reined them in

from speculative bets that could’ve crippled their balance sheets and hurt their customers.

Banks of all sizes, including regional banks, credit unions as well as bulge bracket firms, decried the legislation, claiming it hobbled them with unnecessary paperwork and prevented them from

serving their customers. President Trump promised to ‘do a number’, on the bill, and succeeded in doing so as Congress voted to approve a new version in May 2018 with far fewer limitations and bureaucratic hurdles. Meanwhile, the FSOC and the CFPB are shadows of their former selves.

Still, you can’t argue that the banking system is healthier and more resilient than it was a

decade ago. Banks were over leveraged and over-exposed to house-poor consumers from

2006-09, but today their capital and leverage ratios are much stronger, and their businesses are less complex. Banks face a new set of challenges today centered around their trading and traditional banking models, but they are less at risk of a liquidity crisis that could topple them and the global financial system. Banks stocks, however, have yet to regain their pre-crisis highs.

2. Reducing Risk on Wall Street

Beyond Too Big to Fail was the issue that banks made careless bets with their own money and sometimes in blatant conflict with those they had made on behalf of their customers. So-called ‘proprietary trading’ ran rampant at some banks, causing spectacular losses or for their books or for their clients. Law suits piled up and trust eroded like a sand castle in high tide.

The so-called Volcker Rule, named after former Fed Chair Paul Volcker, proposed legislation

aimed at prohibiting banks from taking on too much risk with their own trades in speculative markets that could also represent a conflict of interest with their customers in other products.

It took until April of 2014 for the rule to be passed – nearly 5 years after some of the most storied institutions on Wall Street like Lehman Bros. and Bear Stearns disappeared from the face of the earth for engaging in such activities. It lasted only four more years, when in May of 2018, current Fed Chair Jerome Powell voted to water it down citing its complexity and inefficiency.

Still, banks have raised their capital requirements, reduced their leverage and are less exposed

to sub-prime mortgages.

Neel Kashkari, President of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank and former overseer of TARP

(The Troubled Asset Relief Program), had a front row seat to the crisis and its aftermath.

He still maintains that big global banks need more regulation and higher capital requirements. This is what he told Investopedia:

"Financial crises have happened throughout history; inevitably, we forget the lessons and repeat the same mistakes. Right now, the pendulum is swinging against increased regulation, but the fact is we need to be tougher on the biggest banks that still pose risks to our economy."

3. Overzealous lending in an Overheated Housing Market

The boiler at the bottom of the financial crisis was an overheated housing market that was stoked by unscrupulous lending to un-fit borrowers, and the re-selling of those loans through obscure financial instruments called mortgage backed securities that wormed their way through the global financial system. Unfit borrowers were plied with adjustable rate mortgages that they couldn’t afford as rates rose just as home values starting declining. Banks in Ireland and Iceland became holders of toxic assets created by the bundling of flimsy mortgages originated in places like Indianapolis and Idaho Falls.

Other banks bought insurance against those mortgages creating a house of cards built on a foundation of homebuyers who had no business buying a home, mortgage originators high on the amphetamine of higher profits, and investors who fanned the flames by bidding their share prices higher without care or concern for the sustainability of the enterprise. After all, home prices continued to rise, new homes were being built with reckless abandon, borrowers had unfettered access to capital and the entire global banking system was gorging at the trough, even as the stew turned rotten. What could go wrong?

Nearly everything, it turned out. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government sponsored entities that underwrote much of the mortgage risk and resold it to investors had to be bailed out with taxpayer money and taken into receivership by the federal government. They are still there today, incidentally. Foreclosures spiked, millions of people lost their homes, and home prices plummeted.

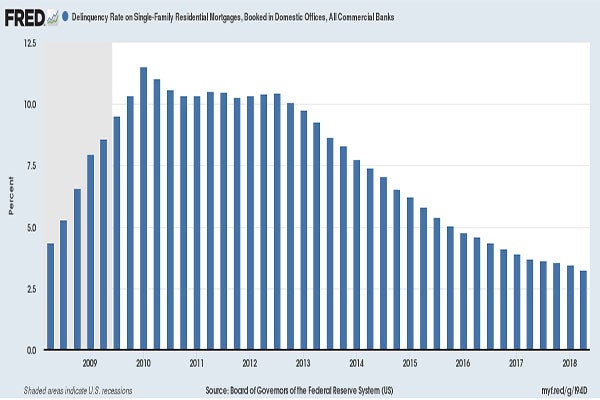

Chart: Delinquency Rate on Single Family Residential Mortgages, Booked in Domestic Offices, All Commercial Banks, Chart Source: FRED, St Louis Federal Reserve

Ten years on, the housing market has recovered in several major cities and lending has become more stringent, to a degree. Markets like Silicon Valley and New York City have boomed as the Technorati and Banking sets have enjoyed a raging bull market and sky-high valuations. Cities like Las Vegas and Phoneix are still trying to claw their way back, and the rust belt has yet to recover.

Today, borrowers are not as exposed to adjustable rates as they were a decade ago.

According to JP Morgan, just about 15% of the outstanding mortgage market is at an adjustable

rate. Interest rates are much lower than 2008, so even future increases are not likely to topple

the market.

That said, while lending standards have tightened, at least for homebuyers, risky lending still

runs rampant for automobiles and short-term cash loans. In 2017, $25 billion in bonds backing subprime auto loans were issued. While that’s a fraction of the $400 billion worth of mortgage backed securities issued, on average, annually, every year, the lax underwriting standards for

autos are eerily similar to the risky mortgages that brought the global financial system to its knees a decade ago.

4. Moral Hazard? What Moral Hazard?

The natural reaction to crises is to look for someone to blame. In 2009, there were plenty of

people and agencies to paint with the scarlet letter, but actually proving that someone used illegal means to profit off of gullible and unsuspecting consumers and investors is far more difficult.

Banks behaved badly – not all - but many of the most storied institutions on Wall Street and Main Street clearly put their own executives’ interests ahead of their customers. None of them were charged or indicted with any crimes, whatsoever.

Many banks and agencies did appear to clean up their acts, but if you think that they all got

religion after the financial crisis, see Wells Fargo.

Phil Angelides headed up the Financial Inquiry Commission following the crisis to get to the

root of the problems that allowed it bring the global economy to its knees. He tells Investopedia he is far from convinced any lessons were learned that can prevent another crisis.

“Normally, we learn from the consequences of our mistakes. However, Wall Street - having been spared any real legal, economic, or political consequences from its reckless conduct - never undertook the critical self-analysis of its actions or the fundamental changes in culture warranted by the debacle which it caused.”

5. How are we invested today?

Investors have enjoyed a spectacular run since the depths of the crisis. The S&P 500 is up nearly 150% since its lows of 2009, adjusted for inflation. Ultra-low interest rates, bond buying by central banks known as quantitative easing and the rise of the FAANG stocks have added trillions of dollars in market value to global stock markets. We’ve also witnessed the birth of robo-advisors and automated investing tools that have brought a new demographic of investors to the market.

But, what may be the most important development is the rise of exchange traded products and passive investing.

ETF assets topped $5 trillion this year, up from $0.8 trillion in 2008, according to JPMorgan.

Indexed funds now account for around 40 percent of equity assets under management globally. While ETFs offer lower fees and require less oversight once launched, there is a growing concern that they will not be so resilient in the face of an oncoming crisis. ETFs trade like stocks and offer liquidity to investors that mutual funds do not. They also require far less oversight and management, hence their affordability. ETFs were relatively new in 2008-09, except for the originals like SPDR, DIA and QQQ. Most of these products have never seen a bear market, much less a crisis. The next time one appears, we’ll see how resilient they are.

It's crazy to imagine, but Facebook, the F of the FAANG stocks, did not go public until 2012. Amazon, Apple, Google and Netflix were public companies, but far smaller than they are today.

Their outsized market caps reflect their dominance among consumers, to be sure.

But their weights on index funds and ETFs is staggering. Their market caps are as big as the bottom 282 stocks in the S&P 500.

A correction or massive drawdown in any one of them creates a whirlpool effect that can suck passive index or ETF investors down with it.

Conclusion

The lessons from the financial crisis were painful and profound. Swift, unprecedented and extreme measures were put into place by the government and the Federal Reserve at the time to stem the crisis, and reforms were put into place to try and prevent a repeat of the disaster. Some of those, like insuring that banks aren’t too big to fail and have ample cash reserves to stem a liquidity crisis, have stuck. Lending to unfit borrowers for homes they can’t afford has waned. But, broader reforms to protect consumers, investors and borrowers have not. They are in the process of being repealed and watered down as we speak as part of a broader deregulation of the financial system.

While there may be a general consensus that we are safer today than we were a decade ago,

it’s difficult to really know that until we face the next crisis. We know this: It won’t look like the

last one – they never do. That’s the thing about crises and so-called ‘black swans’. Cracks begin

to appear, and before anyone is ready to take a hard look at what is causing them, they turn into massive tectonic shifts that upend the global order.

As investors, the best and only thing we can do is to stay diversified, spend less than we make,

adjust our risk tolerance appropriately, and don’t believe anything that appears too good to be true.

#StaySmart

Caleb Silver - Editor-in-Chief

SHARE

SHARE